what’s in a velvet?

Reading the data in a square of velvet.

Now that the first velvet samples have been woven, it’s possible to look back and trace the knowledge and experiences that can be seen in the cloth.

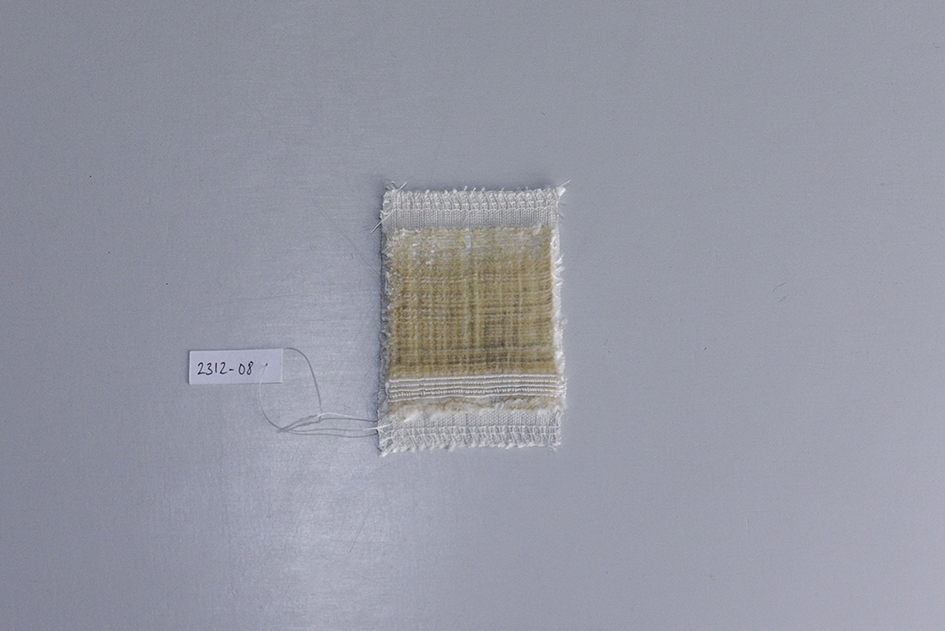

Sample 2312-08 fits in the palm of my hand. In total, it measures just 5 x 8 cm. If you take away the selvedge you’re left with 4,5 x 5,5 cm of woven velvet. Sample 2312-08 feels older than it is. I’m not sure if it’s the yellow effect created by cutting through white silk, the fragility suggested by some of the uneven tufting and stray threads, or the overall smallness of it; although only one month old, this square of silk velvet feels a bit like a relic. It’s the kind of object that makes you want to wash your hands before touching it, to stroke it lightly, and to hold your breath as you lower your head to inspect it.

Sample 2312-08 is an object: a textile manifestation of the preceding six months of research, learning, prototyping and crafting. But it is also a source of information: a physical data bank in which I can trace hypotheses, processes, results, and evaluations.

how to read velvet: a guide

- When reading a sample of velvet, always begin at the bottom-left. This represents the start of the velvet, where the first warp thread meets the first row of weft.

- Work your way from left to right until you reach the end of the row.

- Then move up one row and start again moving from left to right.

- Continue in this way until you have reached the top-right: you have now read the entire sample.

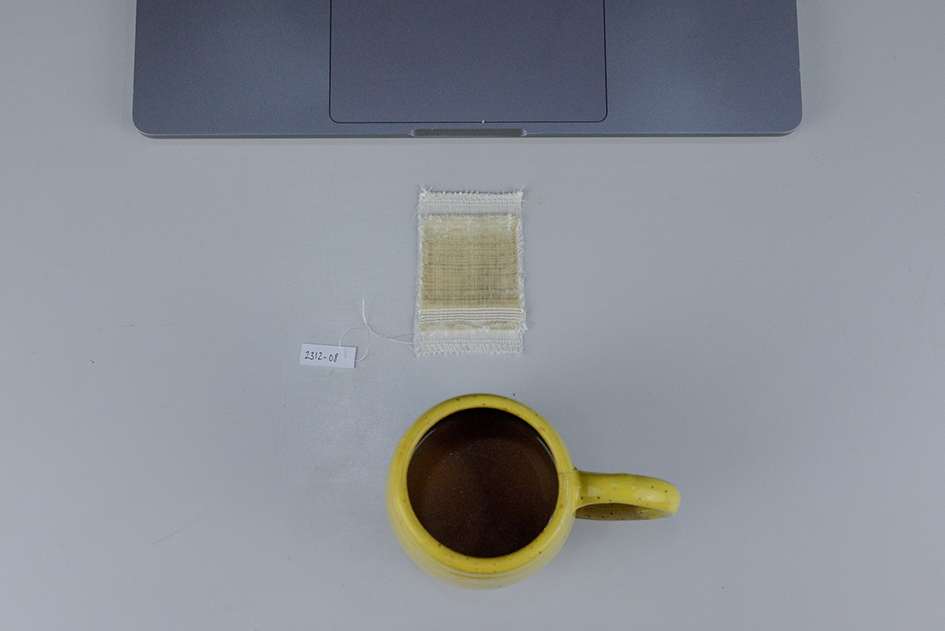

- It is recommended to place the velvet in front of you, between yourself and your keyboard as you craft your written analysis, so as to keep all data directly to hand.

the first rows

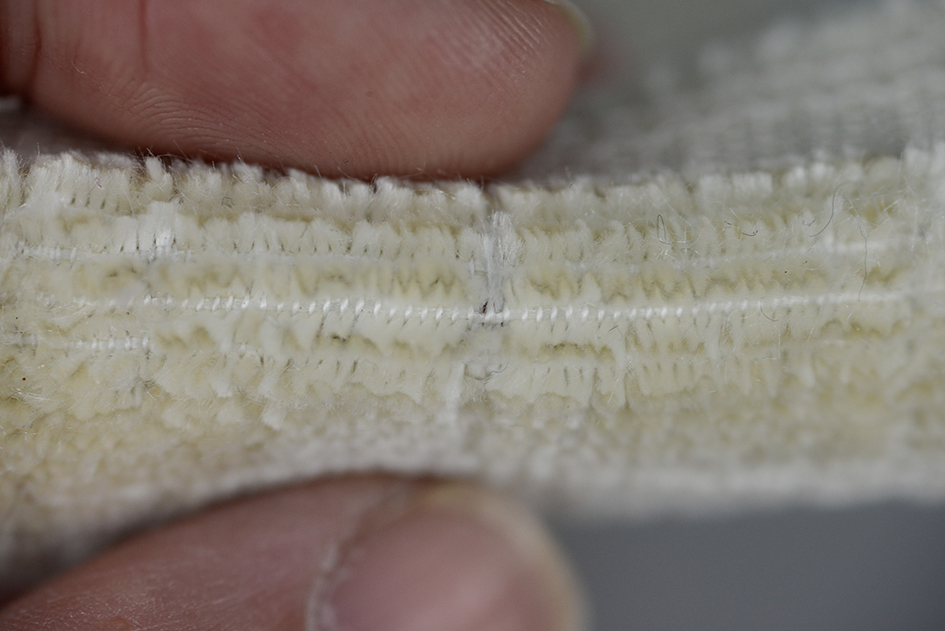

After weaving the header cloth (a strip of plain weave cloth to ensure all yarns are secured and there are no threading errors), Sample 2312-08 shows how I went straight into producing tufted (cut) velvet. The results, as read in the first two rows of cloth, are instantly humbling. The velvet presents a pair of unevenly-tufted rows, inconsistent in both pile height and cut direction.

In the first row, the velvet pile disappears in two locations (right near the beginning at the left, and then just over halfway across the row). The disappearing pile areas are bordered on both sides by longer tufts which don’t stand erect but fall to the front. This particular combination represents where the cutting blade would catch and “skip” over a number of loops. When this occurs, the affected loops are pulled instead of sliced; this loosens and lengthens some loops and shortens others.

In the second row, the pile is cut all the way across but it undulates instead of running in a smooth horizontal line. These changes of direction are a response to the irregular pile height in the first row. If the blade “skipping” over some rows creates an uneven pile, then stopping and resetting the blade at the first sign of resistance may prevent this. The results of the second row of velvet data demonstrate that whilst this approach does indeed prevent the “skipping” effect, it creates new errors. Each time the blade stops and is removed from the pile, the brass rod holding the loops in place is minutely moved. As I bring the blade back to the velvet and attempt to rediscover the rod’s groove, I shift it more, causing it to rotate. The blade follows the rod along this journey of rotation each time I stop and start, resulting in the wavy, uncertain lines.

These first two rows are markers of my inexperience and lack of confidence in velvet weaving (or perhaps misplaced confidence?). They communicate that I don’t yet know my tools well enough and that I haven’t given the silk the stable environment it needs to become velvet.

(Here I take a break to wash my hands. I just ate a Twix and don’t dare touch the velvet.)

looped rows

The next five rows are a factory reset. Each row has been looped around a brass rod but has not been cut. These rows allow me to error-check the velvet loops, testing them for even height, density and stability. They provide both physical and emotional distance between the first two rows of velvet and what will come next, allowing me to proceed with a clean slate of data and a clear mind.

velvet block

The largest block of data in Sample 2312-08 follows the factory reset shown in the looped rows. The velvet at the beginning of the block is smooth and even, the rows are barely distinguishable from each other. In the smoothness and uniformity of these rows I can see the results of two new approaches:

Firstly, I changed my blade. As the blade “draws” across the brass rod, I had instinctively used my pen scalpel as the initial tool. Its small blade makes for precise cutting, and the pen-style body makes it easy to grip and manoeuvre. But in practice, I treated it too much like a pen, not enough like a blade. I switched to the only remaining sharp blade I had to hand: a double-sided blade from a ceramic hob scraper. These blades are thin and broad: I thought the weight distribution across a longer blade length might result in more even cuts.

Secondly, I altered my breathing. In the first two rows, my own nervousness meant I unintentionally held my breath whilst cutting. These resulted in a tension in my body: a tightness in my shoulders, arms and hands passed down to my blade, and then along to the velvet. In the first rows of this block of velvet data, I intentionally focused on my breath, matching a long, slow cut with a long, slow exhale. Continuous breath supported continuous motion as the new blade moved from one end to the other without pause.

In these first few rows of the velvet block, I can also see relief. It’s harder to trace this in the velvet as tangible data – I know the data is there because I have the memory of the emotional experience. I’ve spent quite some time staring at the rows of information, trying to find the pattern that indicates the sense of relief that came with each cut. I haven’t clearly identified it yet, but it’s something I keep coming back to.

As I move up the block of velvet, I can trace an acceleration of weaving speed. As I become more confident in the ability of my breath, hands and blade, I cut the rows more efficiently, with less time to fuss over the infinitesimal placement of each rod. The result is a series of striations which continue to the end of the block. These rows remind me of the lines of metamorphic rock created by the high pressure. The pressure of successive rows of velvet compresses the tufts together. Each striation shows the release of pressure from that row, where the compacted silk threads have been sliced open and given space to breathe.

These striations can also be a result of the tools and the means of their crafting. The brass rods which guide the blade have been grooved by hand using an analogue mechanical process. The slight deviations in the groove caused by this manual process mean the rods do not provide a perfectly straight line. This is especially true at either end of the velvet rods, and evidence can be found in the right-hand side of the velvet block. The cut striations curve slightly upwards, following the oh-so-slight curve found in the rod.

The data in the velvet block can be read not only horizontally (from left to right), but also vertically (from bottom to top). Starting at the base of the velvet block and moving upwards, there are subtle grey vertical marks. These are the remnants of past warps: a build-up of grease and dirt lodged in the dents of the reed. The purity of the white silk and density of the velvet leave no place for these traces to hide, and through this data the reed sends a clear message: Clean me.

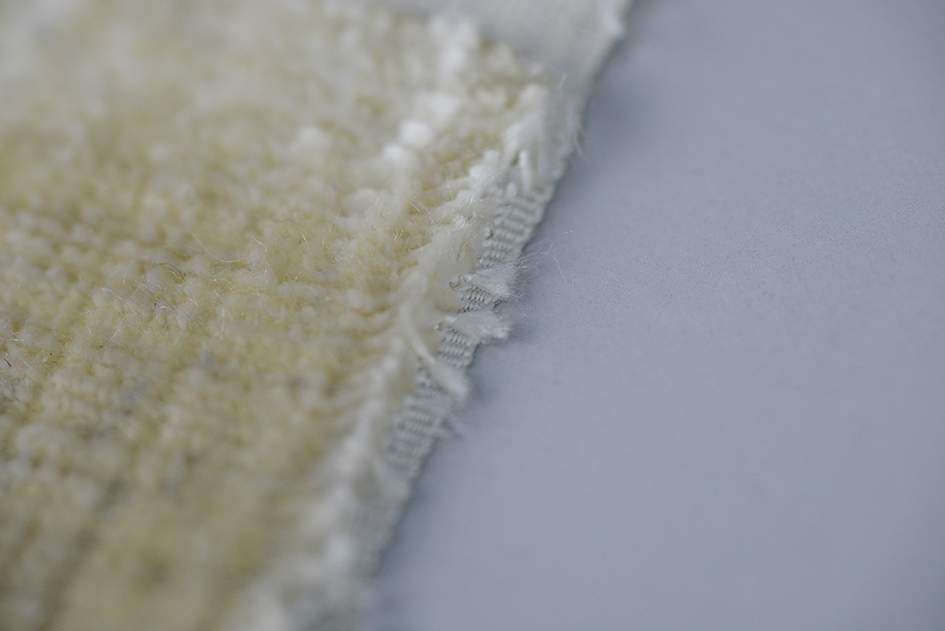

reflecting back: edges

(All good reflections start with a cup of tea. I begin this section by boiling the kettle.)

The edges of the velvet block provide a chance to reflect on rows past woven. Stragglers, individual tufts of velvet stick out at odd angles. During weaving, the outermost velvet threads on either side of the warp are lifted by the brass rod, but are not pulled back down into position by the ground weft, as they should be. As a result, these threads tend to lie flat across the velvet rod, creating vulnerability in the loops and tufts as they are cut. These stragglers impact the rows that come before and after them, and the velvet threads that neighbour them.

As the block of velvet progresses and I begin to understand this, two things happen in response: the selvedge becomes narrower and the stragglers begin to reduce in number. With practice, I learn to go against one of my strongest instincts as a weaver: not pulling the weft thread too tightly against the selvedge. This can put undue pressure on the outermost selvedge threads causing them to break. Yet velvet requires pressure, it thrives on it. So I begin to pull the ground weft tighter and tighter, forcing it to draw the outermost velvet threads into their intended position. The selvedge doesn’t break as I’d feared; it remains stable and the outer velvet threads can be cut in harmony with the rest of the ends.

The edges are a good reminder that velvet threads are not clones of each other, but that each is unique. Velvet is a cloth where each cut tuft is dependent on its neighbours for survival: the rows below and above, the threads left and right. When a tuft does not have one of these crucial supports, the weaver must find a way to compensate. These outermost velvet threads speak the same language as the central threads, but with a different dialect. In adapting myself as a weaver I expand my velvet vocabulary to learn to talk to these outer threads and understand what they need.

final rows

The final rows of the velvet block highlight the gaps in my own knowledge and experience and the learning curve I have yet to master.

The tufts continue to be reliably cut, as the new blade and breathing pattern are still employed. Yet the density between rows shifts drastically and I can see the exposed ground warp. These gaps between the rows are caused by the warp being wound forward. When this happens, all the tension held in both the ground and velvet warps is released. The warp is then rolled slowly onto the front beam before the tension is taken up again.

This sudden shift in tension has a profound effect on the velvet threads: they are disturbed and for the rest of Sample 2312-08 I am unable to settle them. There is a precarious looseness in the tufts as they hold together (but only just). This fragile instability is a strong reminder of how the velvet tufts are co-dependent. They need each other for support, they struggle to exist without close contact on all four sides.

tl;dr

Sample 2312-08 is one piece of woven velvet divided into the five sections described above. The first rows are the alpha test, an initial attempt to see if the velvet process I prepared would perform as expected. The loops are a reset back to the beginning, and the large block shows the most consistent performance of velvet weaving. The edges provide an opportunity to look at the velvet data being gathered in real-time and adapt the process to generate more precise results. The final stages of the velvet present a new problem to be solved: how to support the velvet as the warp is wound forward.

And now? I can make a fresh cup of tea, turn over Sample 2312-08 and read the data again, this time on the reverse. What do you see?

Datenschutzerklärung — Impressum

©Emma Wood 2025